The Spiritual Practice of Prayer

A friend told me recently that he appreciated this series of articles about the spiritual disciplines, which was nice to hear. He went on to say, “But I don’t like the word discipline.”

Perhaps no other aspect of Christian life has been subjected to more legalistic application than have the spiritual disciplines. This means a careful examination of the practices is suspect from the beginning.

A nationally acclaimed minister told me, “Look, ‘spiritual discipline’ is not a biblical term. You’re teaching heresy.”

I replied, “You’re correct. The word ‘spiritual’ and the word ‘discipline’ do not appear side-by-side in Scripture. But your literalness avoids, excuses, perhaps denies, the force of Scripture to guide our lives. Paul said to Timothy, ‘Discipline yourself for the purpose of godliness.’ Perhaps we should rename these practices the ‘godly disciplines.’”

You are free from the religious instruction teaching that you must in order for God to. You are free from trying to get close to God. You have been brought close to God by the work of Christ. As the Bible puts it, you are free from the law.

But these declarations of belief regarding freedom in Christ pertain to legalism not godly practice.

Granted, you can take almost any Scripture and turn it into a legalistic requirement, including the spiritual disciplines. Doing this doesn’t make the principle or practice wrong. It identifies a flawed motive based in fleshly effort.

Scripture declares that as a new person in Christ you are created to perform good works. Transformed by the redemptive work of Jesus Christ, you are designed to function—to perform—according to God’s original intention.

It is true that you are free from a performance-based acceptance with God. It is also true that you are free to perform according to your spiritual design—and this freedom-by-design requires discipline to bring freedom into life.

Ann Voskamp puts it this way: “Daily disciplines are doors to full freedom.”

Still, the Bible is candid about discipline: “All discipline for the moment seems not to be joyful, but sorrowful.” Paul reports “buffeting” his body, training like a boxer, winning, and running with endurance.

When it comes to discipline, the question is not should you discipline yourself, but how and why.

The answer is simple yet profound.

You discipline yourself as Christ disciplined Himself because doing so enables you to realize—to recognize, perform, and enjoy—your heart’s true desire. And what does your new, redeemed heart desire? More than anything, you desire to genuinely know—not know about, but sincerely know—and understand your heavenly Father, God.

As I have written previously, Richard Foster gives the word picture of the Christian life being like a mountain path. On one side of the path is a precipitous drop into the depths of legalism, i.e., performance-based acceptance with God. On the other side is the dark valley of license, i.e., taking impudent advantage of God’s grace in justification to follow after sin’s enticements. But on the path, which Foster identifies as the spiritual disciplines, is where your heart longs to be because it is on the path that you encounter God. Walking with God, you grow to know God, to understand how He thinks, operates, loves, and persists in lovingkindness.

The spiritual disciplines, the spiritual practices, are the path that places you in position to realize your heart’s desire.

From this vantage point, the disciplines are not onerous burdens of religious requirement. They are the means to a desired end.

The spiritual practices set you free to fly with God. In the imagery of Plato, the spiritual disciplines return to your soul the wings that were lost to you as a descendant of Adam. In the poetry of David, the disciplines are where God gives him feet like a ram enabling him to scale heights his enemies can’t climb. Habakkuk used the same imagery to console his soul with the impending invasion of the Chaldeans.

Like the other spiritual practices, prayer is neither obligation nor regulation. Rather, prayer is the active, conversational engagement of your heart and soul with the heart and soul of God.

Prayer as a discipline is nothing more than a regular, habitual pattern of conversation with God—a relational default that is so routine for you that it is your normal disposition as you approach each day’s demands. When Scripture says, “Pray without ceasing,” this practice is the application.

How then should you pray?

Some prayers are formal, others casual. Some are thoughtful. Some intimate, caring, and tender. Some are serious and some hilarious. Some are voiced, some are thought. Some have words and others do not. Our relationship with God completely encompasses all that we are, all that is in our hearts to say, and all that our souls can conceive.

My buddy Ralph Harris writes about, “Loud prayer. Angry prayer. Sloppy prayer.” He says, “I’ve learned I’m safe to express the terribles and awfuls and dreadfuls to God, who proves He is the antidote in me for the poison I’m experiencing.”

When Jesus’ disciples said, “Lord, teach us to pray,” He obliged them with a form, an outline: “When you pray, say, ‘Father, hallowed be Your name. / Your kingdom come….’”

The opening prayer of the liturgy reads, “Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit: as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever. Amen.”

As Peter is drowning, he prays, “Lord, save me!” The outcast woman prays, “Lord, help me!” Offended and indignant, Martha prays, “Lord, do you not care?”

How do you pray?

John Piper writes, “Pray to the Father in the name of Jesus by the power of the Holy Spirit. This is the general form of prayer in Scripture. But, from time to time, ’Maranatha! Lord Jesus come!’ is not a bad prayer.”

The point is not how you approach God in prayer but that you come to Him.

God is no more impressed with, “Almighty God, maker of heaven and earth,” than He is put off with a wrenching, “Oh, God! Please help me.”

Ralph writes again, “My prayers with God are conversational, not formal. And in that, there is room for calm, gentle, quiet and listening, as well as for volume adjustments, hand waving, fiery feelings, bad grammar, and bad vocabulary. That’s all there because that’s all me with God. He knows me at every moment already, so I don’t change myself to create a better moment.”

Our theology states that Christ is in God, we are in Christ, and Christ is in us. For this position to be altered or tarnished would require that God change His mind, which He set ahead of time before laying the foundations of the world, or that the finished work of Jesus Christ become unfinished.

Therefore, you can speak and pray, you can think and pray, you can pre-dispose yourself for an event and pray. In fact, you can utter unintelligible sounds and Scripture says the Spirit prays for you in your groanings.

Brennan Manning says, “A little child cannot do a bad coloring; nor can a child of God do bad prayer.”

God says, “Come.” He tells us to pour out our hearts to Him. He literally instructs us to “fling our concerns in His general direction,” so there’s no need to even organize your prayer. The humility of God is that He stoops to where we are rather than requiring us to rise where He is.

Willink and Babin teach that a good leader is not put off by questions. In fact, good leaders expect and invite questions and conversation.

If this is true of earthly leaders, then it is certainly true of God. He invites our questions, even our disagreement. He challenged Job to debate Him and Isaiah to argue with Him.

Yes, God is God, King of kings, and Lord of lords. But He also is our Father. Scripture says the Spirit guides us to call Him, Abba/Daddy.

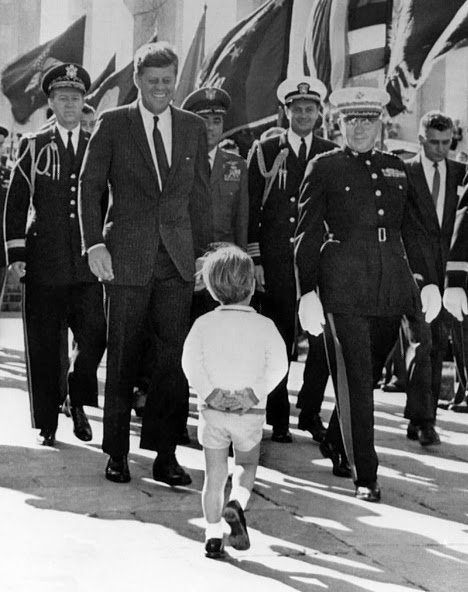

Do you recall the photographs of John Jr. with his dad, President John F. Kennedy? The pictures provide an earthly inkling of our heavenly relationship with God. Just as a child is not obligated by formality with their father, neither is a child of God constrained with their heavenly Father.

Ask. Seek. The force of the grammar is to keeping asking and keep seeking. Continuously. To the extent you can understand, God wants you to know and understand Him and His ways.

Let’s face it though: God knows everything. So, what’s the point of prayer?

Obviously, you don’t pray in order to inform God or update Him on your life. Thus, from God’s vantage point, the only possible reason for you to pray is that He loves interacting with you. All you have that God needs is you. So, come. Pray.

Do you ever call your spouse just to hear their voice? Do you ever pray just to hear God’s voice, and Him yours?

Willink and Babin go on to say that while great leaders entertain questions and even debate, sometimes a question can’t be answered and a plan won’t be changed.

There are biblical instances of prayer where persistence results in the prayer’s desired outcome. But, the majority of prayers asking for a particular outcome are not answered according to the prayer’s wishes.

The Bible reports that Daniel prayed for protection when cast into the lion’s den. God responded and shut the mouths of the lions. But history records countless Believers were fed to the lions and died torturous deaths. Is there any doubt these folks prayed with faith, believing God for protection, even while their bodies were being torn asunder?

Prayer is not a potion. Prayer is not magic. Prayer is not a posture. God doesn’t hear a kneeling prayer better than He hears a desperate prayer or a grateful prayer at mealtime.

Prayer is a relational exchange between you and God. Since you and God are never separated, there is no such thing as unanswered prayer. God would not tell you to come to Him only to turn away and ignore you.

My encouragement is to be careful how you define answered prayer. Sometimes God’s answer is a torrent, at times a nod, and often the intimacy of silence is plenty of reply.

While God always answers, God does not always answer as you hope, wish, or plead for in this life. God responds to every prayer, but on His terms and with His foreknowledge.

Ask, in faith, trusting, but understand that God’s answer may be beyond your pay grade.

Recall that Jesus, the perfect man, prayed in the Garden of Gethsemane. His human prayer was so fervent, so anguished, that He sweat anxious drops of blood.

Note that Jesus prayed the same prayer, “Father, deliver me,” multiple times. Even Jesus’ persistence in prayer did not render the desired outcome. Realizing what was coming, He prayed passionately for an alternative plan—and was crucified anyway.

So, telling God repetitively, and with energy, what’s on your mind is fine.

God knows the ultimate plan and you do not. Therefore, it is imperative in your praying to trust the wisdom and goodness of God lest you believe yourself slighted and abused by an indifferent deity. God is good, and He must be good all the time or He is not good at all. However, just because He is good doesn’t dictate that His answer will be to your liking.

Have you considered what would have transpired if God answered Jesus’ prayer as He requested?

For all of His sweating and anguished prayers for deliverance, Jesus also declared His trust in God’s foreknowledge: “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup [of suffering and death] from me; yet not my will, but yours be done.”

In practicing prayer, especially when I’m anxious or sense an impending trauma, it is healthy for my soul to follow my Older Brother’s practice in prayer and say, “Father, I’ve expressed my opinion and I thank you for hearing my prayer. However this works out, I trust you and your good will toward me.”

Like the Preacher taught in Ecclesiastes, James notes the futility of arrogantly making plans as if our lives are ours to foreknow and manage. He counsels us to pray this way: “If the Lord wills, we will live and also do this or that.”

The commanding, insisting, believing, declaring prayer of positive confession taught by some teachers is problematic, sincerity notwithstanding. The disrespect of demanding that God do what you declare; the arrogance of believing you know enough, are insightful enough, or are sufficiently prescient to command God’s conduct: I wince at these prayers.

Psalms recalls that Israel became demanding of God when they were in the wilderness. They tempted Him, no doubt taunting Him to answer their demands. So, God answered their demand… but sent a wasting disease among them.

God invites us to come to Him with any concern and approach freely, like a child does their father. But any healthy relationship hinges on mutual respect.

James instructs us to pray with faith. Asking. Believing. Not doubting. Failing to pray with confident belief results in a tumultuous lack of resolve, like waves lapping the seashore. In fact, a doubting prayer is an ineffective prayer. Father God wants us to confidently come to Him with transparent honesty. We are His children. Christ is our Brother. The Spirit is our Help. Doubting this renders us doubleminded and unstable because it is an affront to God’s redemption of us.

How you approach God in prayer is indicative of what you believe about God and about yourself.

As you read in my article on the spiritual practice of fasting, in March of 1982 I began a daily, 24-7 odyssey with physical pain. Over the years, I’ve seen every type of practitioner you can name and a lot you’ve never heard of. I’ve been exorcised, dieted, exercised, anointed, stretched, stuck, struck, burned inside and out, popped, pressurized, frozen, heated, immobilized, anesthetized, categorized, demonized, sanctioned as a remorseless sinner, and been more demoralized at times than you want to know about.

I’ve sweat through my clothes resisting pain on more occasions than I can number. I’ve cursed, and cried, and cajoled. I’ve stood by the airplane bathroom, smelling that smell, over thousands of miles, to more destinations than I can count because it hurt too badly to sit down. Not even the dog was faithful enough to sleep with me when I began my nightly tossing and turning.

I’ve prayed every prayer, read all the right books, and felt the hands of those gifted with biblical miracles of healing and prophecy pleading with God for my healing and deliverance. Nothing.

I’ve declared in faith, walked in faith, believed in faith, professed in faith, and to date am denied relief though still believing. I’ve tried thanking God, rejoicing in all things, yielding my rights, and wielding the sword of the Spirit against the dark adversaries in unseen places who torment my physical frame. Nothing.

For me, one who practices prayer, sincerely praying, “Father, not my will but yours be done,” has been a torturous disposition to acquire and at times remains a tenuous hold.

But now, more often than not, after years of practicing prayer, I can locate this sincere footing within my soul. Over time, this difficulty has become a high place, like the high place David and Habakkuk spoke of, where my feet are like hind’s feet and I find solitude in the places Father frequents.

Foster is correct. My practice of prayer has resulted in conversations, convictions, and character with Father God that I never would have had if He had answered my prayers for healing in 1982.

The spiritual practice of prayer, like the other disciplines, isn’t intended to achieve an earthly end, but to position you to realize your heart’s ambition: to know God and understand His ways.

One day, like my brothers Mason and Wade, I too shall be released from this life and enter heaven’s gates. Pain will be left behind.

I have little notion of what heaven will be like, although I’m sure it will be fine. But at some point, once inside the pearly gate, my anticipation is Father saying to my Older Brother and me, “Come here. Let’s discuss life. Spirit, make certain my younger son understands, please.” And the waltz of prayer will begin, four friends conversing with no fallen impediment between them.

My hope is that through the spiritual practice of prayer here, my conversation there is a natural, easy transition. You know, like picking up where we left off, but without an, Amen.

Next up: The spiritual practice of soul friendship. Until then, keep your wits about you.